WHAT IS IT?

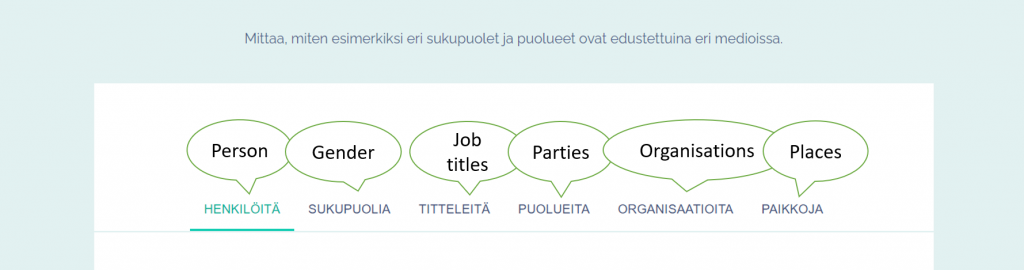

The News Source Diversity Meter is a tool that analyses automatically news content, such as news archives and their metadata. It scans through the texts and identifies all the names there (person as well as organisations and places). It identifies if the person is cited in the text (directly or undirectly) and thus distinguishes the news sources from all person mentioned. The meter also identifies specific information related to news sources (their gender, job title and political party, if it’s mentioned in the text). As search results, the meter provides lists and graphical presentations of news sources, organizations and places that are represented in the texts (see details below). All results can be narrowed by different search criterion such as a topic of stories or period of publication. Currently, the meter is used internally by media companies, and users only receive information about their own news data.

WHICH TECHNOLOGIES DOES IT USE?

The News Source Diversity Meter is based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) technologies and language models (Libvoikko, NER, UD) and hand-written parsing rules.

WHAT DOES IT REVEAL?

As illustrated above, the tool identifies all the people in the text, their gender, their job titles and their political party (if mentioned). Beside that, it also recognizes all organisations and geographical places (cities, towns). It then creates simple statistics out of these diversity dimensions, such as propotions of male/female/unknown news sources or list of job titles in the order how often they appear in the texts.

The meter can categorise the results according to the day of publication or the topic of the article, which enables more precise searches. Searches can be performed on the entire dataset or strongly narrowed set of texts which is sometimes highly useful. Searches can be performed with only one search criterion or a combination of several criterion, which enables for example this kind of question: Who were the most cited politicians during 2021-2022 in the topic of immigration?

The reliability of search results has been validated twice and their accuracy varies between 77-91% depending on the search function (identification of orgnanisations and places being most weak).

MEASURING JOURNALISTIC CONTENT

The reading habits and behaviour of media consumers are closely monitored. Digital distribution channels have provided media companies with a wealth of information on what the public consumes, which articles hold people’s attention, and what they spend their time on. Information about the public’s behaviour also helps to build various recommendation algorithms.

It has been suggested that a similar leap forward in digital technology should also be made in the field of journalistic content analysis as a whole (suomenlehdisto.fi). As society becomes increasingly pluralistic, the diversity and pluralism of journalism in particular have become significant goals in terms of politics and the self-understanding of the media. However, conducting automated analyses of journalistic content has proven complicated.

A study commissioned by the Finnish Ministry of Communications in 2018 found that the available indicators of media diversity reveal the most about the number of media outlets and the diversity of media owners and content providers, as well as the diversity of media consumption for the reasons mentioned above. Conversely, there was no data for measuring the diversity of content, so, ultimately, the proposal was for qualitative indicators based on limited datasets. The same problem has plagued the EU-led Media Pluralism Monitor, which is tasked with evaluating the risks to media diversity in each country. MPM evaluations were developed from 2012 to 2014 and have been carried out since then (since 2015 in Finland), and it has been necessary to reduce the number of indicators focusing on journalistic content due to a lack of available data on several occasions.

However, some innovations have arisen as more journalistic data has become available. One good example is the development towards binary gender equality among people appearing in the media. The most traditional player in this field is the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP), carried out since 1995. The project monitors the share of women and men among the people appearing in the media worldwide. The researchers conduct the evaluation manually using carefully defined material. A few years ago, Prognosis, a Swedish innovation, automated this calculation using an Equality Bot, which reports the proportions of women and men in various online media outlets every day. The first gender meters introduced for media companies themselves hit the news in 2018 (hs.fi). Examples of the most advanced gender meters include the Gender Gap Tracker, a Canadian project based on the same technology as the News Source Diversity Meter. Another similar project is American Press Institute’s tool called Source Matters which supports automated, customizable source diversity tracking.

Tracking news sources is a very daunting task because there are so many variables and the data available is often not commensurate. A good overview of the complexity of the subject has been made by AIJO project. According to them, the diversity of sources can be approached either through photographs (like JanetBot by Financial Times), text (like our meter or Gender Gap Tracker) or data collected by the journalists themselves (like Dex tool by NPR). The fragmentation of the field means that everyone is working on the same challenge on their own – there are few providers of total commercial solutions (see, however, the Ceretai’s Diversity Dashboard). An individual question is how to integrate a good diversity tool as a part of the journalistic culture in different newsrooms. (For example Ringier Group has succeeded here with their EqualVoice project.)

The idea behind the News Source Diversity Meter was to find out who can make their voice heard in journalism. The idea is that by making the media’s source choices more visible, they become easier to develop. As such, it is not enough to know the proportion of women and men being interviewed. It is just as important – or even more so – to know which experts are invited to explain which topics, which bodies in society have their voices heard the most, and which political parties get to have a say on which issues. It is also relevant to distinguish between the weight attributed to sources’ words. For example, does a person appea as one of the sources in a minor story or as the only interviewee in a long-form article?

Journalism research has repedeatly shown that the sources journalists choose to quote in their stories has lot of influence on whose stories get told, how they are told and to who they are told. That’s why tracking sources is so important.

A meter based on machine analysis has only a limited ability to answer such questions. Interpretations and conclusions will remain the domain of researchers and media professionals. Quoting American Press Institute: “It’s not enough just to track source diversity. It also requires community listening, relationship building, time to develop new sources, training and coaching.”